Ancient naval warfare under oars involved the use of galleys propelled by oarsmen, which were primarily designed for close combat tactics like ramming and boarding enemy ships. Despite many Hollywood scenes, to the contrary these ships were not always manned by slaves chained to the hull. This method of naval warfare dominated naval tactics from antiquity until the late 16th century, when square-rigged sailing ships with naval artillery began to take over.

To my knowledge, no accurate accounts of ancient Bronze Age maritime battles exist.

Several fleet battles occurred during the Classical Greek Era, which are reasonably well-documented. The Greek historian Herodotus tells us that the dominant fighting ship of that day which was the wooden Greek or Phoenician Trireme.

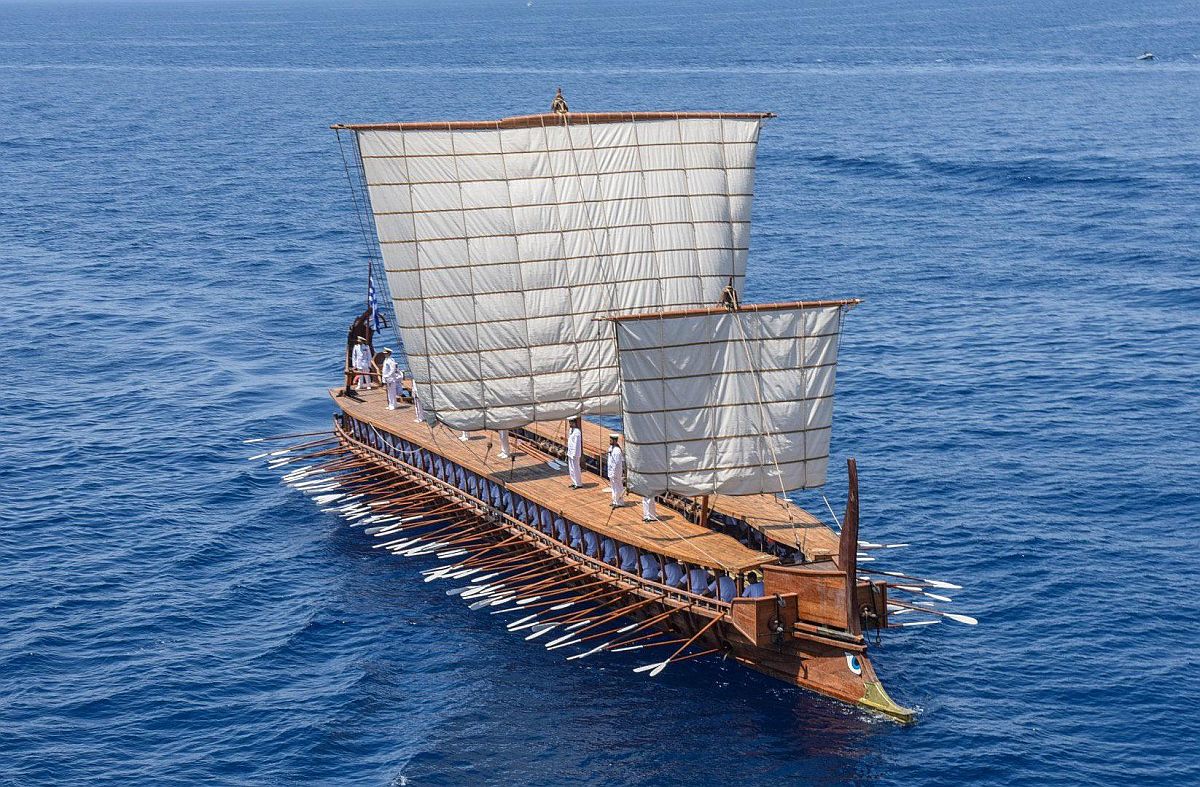

The Trireme – The Queen of Sea in the Classical Greek Era

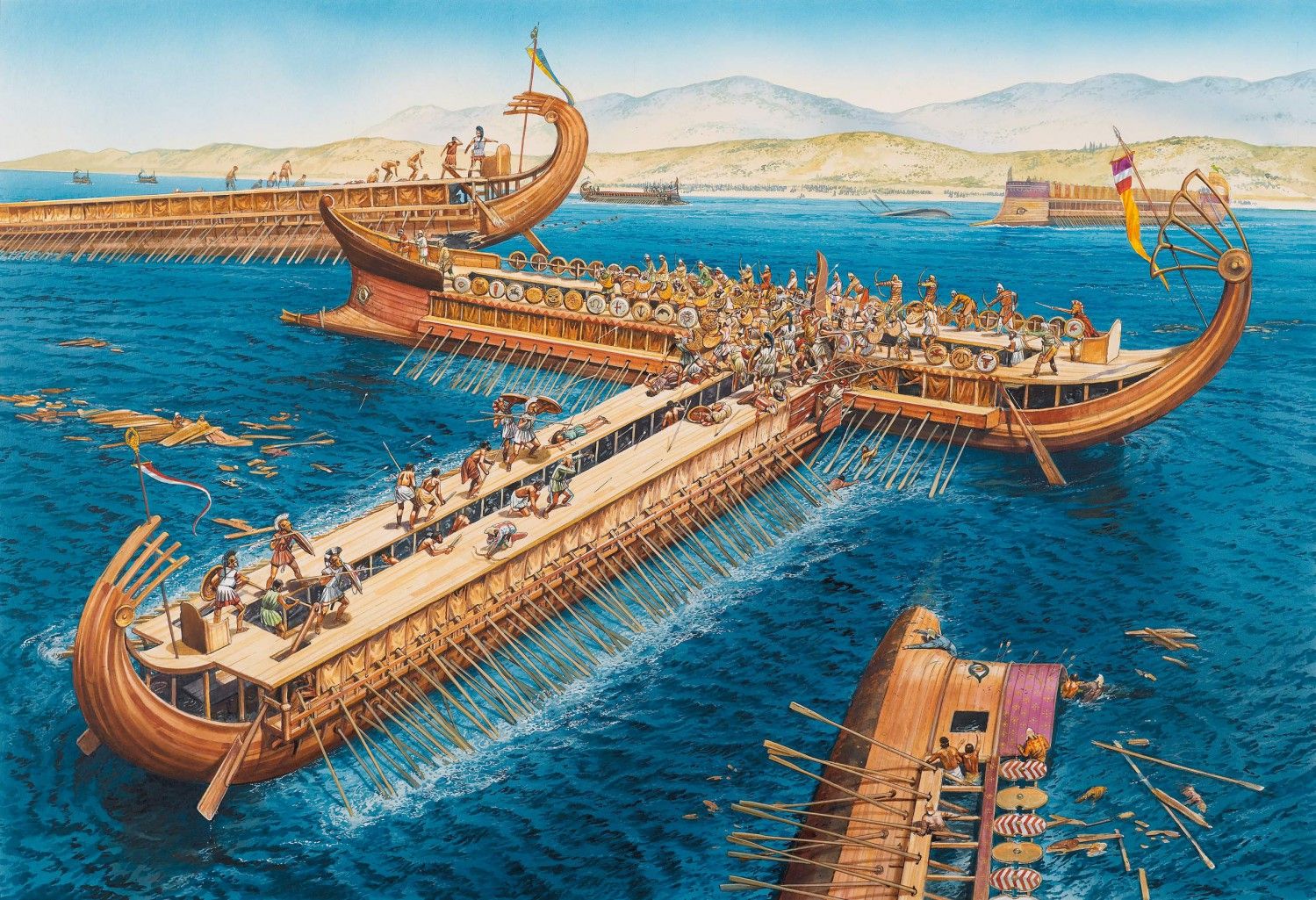

The trireme had three levels of oarsmen. The ships would often sail in substantial fleets. They would routinely sail to the conflict area, and then row into action to oppose the enemy fleet in a line-abreast formation with their ramming prows facing the enemy.

The preferred battle tactic was to ram the enemy ship’s hull in the side of the ship, causing a large hole in the hull, below the waterline. The attacking rammer would then reverse the direction and pull with the oars to back out of the hull of the enemy ship which was sinking. Once the attacker was free from entanglement and had escaped from the sinking enemy ship, the attacker would look for another ship to target in the enemy fleet.

This narrative is about one of the greatest of those classical sea battles. The focus sea battle was fought between the Phoenician naval forces of the mighty Persian, emperor Xerxes, and the underdog Athenian Greek navy commanded by the noble admiral, Themistocles.

The Birth of the Persian Empire:

In the summer of 553 BC the nominal Persian king, Cyrus, joined forces with the disloyal Median general Harpagus. Cyrus led a revolt of the Persians against the Median overlordship of the Median king, Astyages. That revolt culminated in the epic three day long Battle of Pasargadae in 552, in which Cyrus defeated his median overlord and became the actual king of the Persians and the Medes, thus founding The Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus spent the next 6 or 7 years consolidating his reign.

The western half of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) was ruled by the Lydian king, Croesus, who attempted to use Cyrus’s initial weakness as an opportunity to expand the border of his eastern frontier into the formerly Median territory of Cappadocia, in central Anatolia.

As an aside, the Lydian kingdom is also famous in world history because it invented money. The Lydian kings were the first ones to begin minting coins to monetize their trade. Of course, that invention caught on and quickly became universalized throughout the rest of the world. The mythological Greek story about the wealthy King Midas is based on the real Lydian king who first coined money.

Cyrus the Great met the attempted Lydian invasion with his combined army in late 547 BC, and he defeated the Lydian king in The Battle of Pteria, and the subsequent Battle of Sardis (fought at the capital of the Lydian Empire) the following spring. Cyrus famously used the camels which had carried the Persian baggage in the front line of his attack because he had learned that the camel’s odd and unfamiliar smell was disturbing to the Lydian horses which had never encountered it before. Cyrus’s tactic thus created dromedary dismay in the Lydian Calvary and made them useless as a fighting force, which utterly destroyed the effectiveness of the Lydian cavalry, giving Cyrus the victory. Cyrus thereby ended the Lydian Empire and added all of western Anatolia to the Achaemenid Persian Empire, importantly including the Ionian Greek coastal territories along the eastern coast of the Aegean Sea.

Greek & Phoenician Trade and Naval Power:

Greek and Phoenician city states in modern-day Lebanon, had traded with other cultures throughout the Mediterranean, Aegean and Black Sea from at least the mid-9th century BC (the Archaic Greek Era). Both the Greek and the Phoenician traders had established small colonies or trading outposts on natural harbors as widely separated as the Crimean Peninsula, and modern day Marseilles in southern France. The Homeric sagas are based on the wide-ranging Greek merchants of those early days.

The Phoenician sailors were also particularly adventurous and are known to have routinely circumnavigated the continent of Africa. This feat was recorded by the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho-II, and it was proven to be true, unintentionally by the Greek historian Herodotus in 484 BC. Herodotus was asserting that the Phoenicians are liars because they claim to circumnavigate Africa. They say that when one is sailing west off the southern coast of Africa at noontime the sun is on one’s right. Herodotus, who lived his entire life in the Mediterranean region (north of the equator), asserted that this claim proved what liars the Phoenicians were!

Actually, as any modern seafarer understands, that claim by the Phoenicians is a strong proof that they were, in fact, circumnavigating Africa.

The Failed Ionian Revolt Against the Persian Overlords of Ionia:

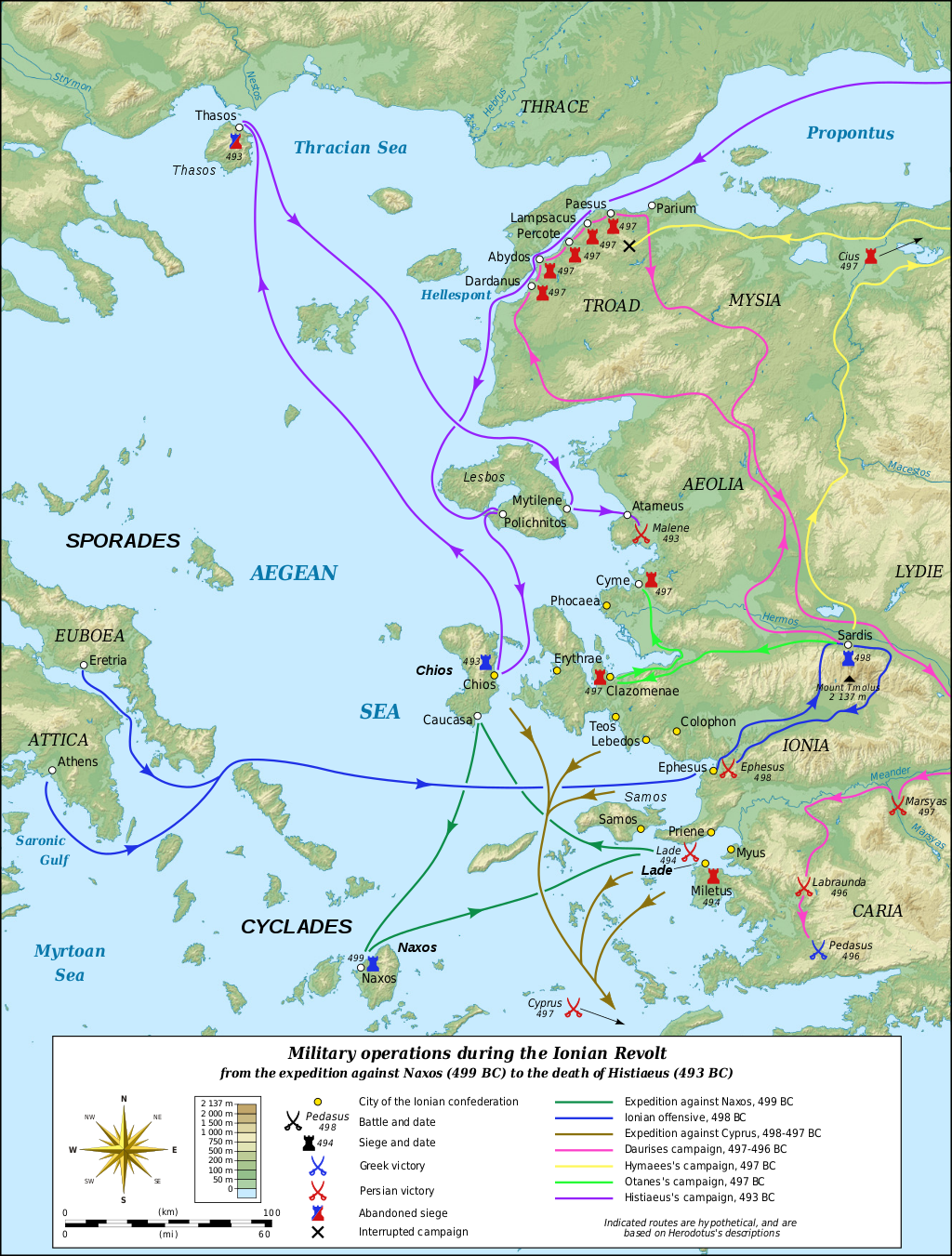

In 499 BC an Ionian Greek named Aristagoras, was the Achaemenid Persian-appointed Greek tyrant (king) of the city state of the Ionian coastal city of Miletus. He launched a joint expedition with the Persian satrap of Sardis (the governor of the capital of the western Anatolian province of the Persian Empire), Artaphernes to conquer the wealthy mid-Aegean island of Naxos. However, the expedition was a debacle and prompted Aristagoras’ dismissal by the Persian satrap. In response, Aristagoras incited all of the Hellenic Greeks of the western coastal region of Anatolia into rebellion against their Persian overlords. The wealthy Greek city-states of Athens and Eritrea provided aide and assistance to The Ionian Revolt, against the satraps of their Persian overlords in Anatolia. In 494 BC the revolt was definitively suppressed by the Persian forces at The Battle of Lade, in Miletus.

The Persia’s Unsuccessful Attempt to Invade Mainland Greece in Retribution

In 492 the Persian emperor, Darius the Great, allied with the Phoenicians for Naval support. He then sent an invasion force into mainland Greece to extract retribution from the Eritreans and the Athenians for their role in helping the Ionian Greeks in their revolt against their Persian overlords.

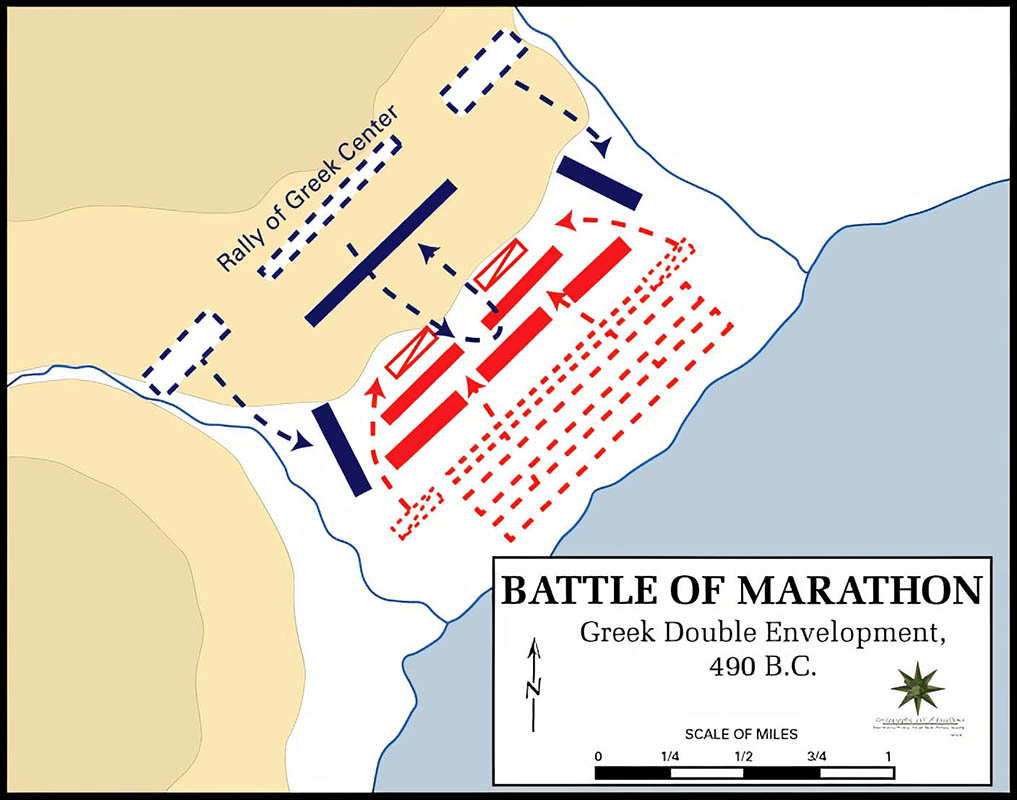

The crescendo of this attack was the famous land Battle of Marathon. The wily Athenian General Miltiades chose the location for the battle, with marshes and mountainous terrain, that prevented the Persian cavalry from being able to join the main Persian army.

When the Persian and Greek forces lined up to oppose each other, Miltiades, ordered a general attack against the entire Persian defensive line. He reinforced his flanks, luring the Persians’ best fighters into his weaker-appearing center. The inward wheeling flanks of well-equipped and disciplined Greek Hoplite phalanxes enveloped the Persian center and severely routed the Persian forces; a classic and well-executed double envelopment tactic. The Persian army broke in panic and ran towards their ships, and large numbers of them were slaughtered. The Greek defeat of a substantially larger Persian force at Marathon marked the end of the first Persian invasion of Greece, and the Persian force retreated to Asia with the help of the Phoenician navy.

The Farsighted Themistocles Built Wooden Walls to Save Athens

After the Greek victory at Marathon most of the Athenians thought their victory against the Achaemenid Persian Empire was complete, and the Persians would not be back. Subsequently, a large vein of gold was discovered on the Attic Peninsula within the territory of Athens. It was on public land so according to laws of the democratic republic of Athens, the gold belonged to the citizens of Athens.

Themistocles was an Athenian statesman, politician and general (admiral). In 483 BC, during a time of peace, when the Athenians were proud that they had defeated the Persians at Marathon and had thus ”won the war,” however Themistocles knew better. He knew that eventually the Persians would come back in greater force. He convinced the Athenians to spend 70% of their gold bounty money to build 200 expensive new triremes (three level rowing, ramming type battle ships) and to train crews to strengthen the Athenian navy in anticipation of a possible Persian return.

480 BC – The Massive Second Persian Invasion of the Greek Mainland – The Persian Retribution Approaches

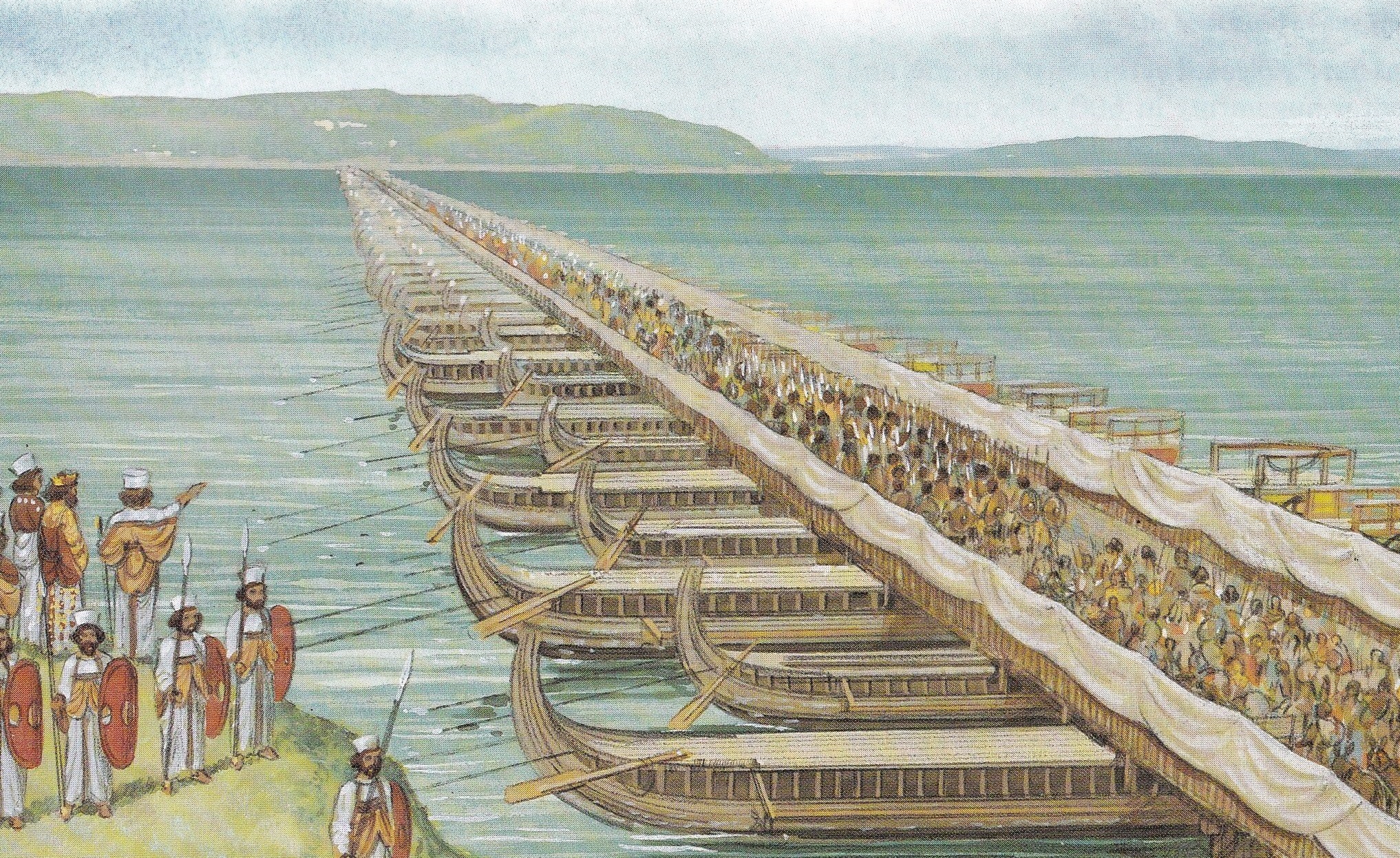

The Persian Emperor Darius the Great had died, but his successor Xerxes was planning an unstoppable invasion force to definitively attack and subjugate Greece. In 480 he had his engineers build a pontoon bridge across the Hellespont (the narrowest portion of the straights between Asia and Europe). He marched a massive army across that bridge and began fighting his way south towards Athens.

The Greeks of The Hellenic League, which included the famous 300 Spartans led by their valiant Spartan king, Leonidas, held the Persians out of the narrow pass at Thermopylae for several brilliant and triumphal days. The fleet of Greek triremes, the navy of the Hellenic League also fought valiantly to defend the narrow straits between the city state of Artemisium and the narrow pass at Thermopylae. Themistocles was the commander of that fleet. The Phoenician fleet working for Persia won the battle but did not pass through the straights which the navy of the Hellenic League was defending.

However despite the brilliantly conducted Greek defense of both the strait and the pass, the massive Persian army and its Phoenician navy eventually prevailed. The Persian army marched onward to Athens. The Hellenic League broke up into to an “every city state for itself” mode and their respective armies marched home to defend their individual cities by themselves.

The Phoenician navy chose to sail towards Athens, passing around the eastern shore of the island of Euboea. A violent Aegean storm damaged and sank many of the Phoenician triremes of the Persian navy as it sailed around the outside of Euboea, trying to reach Athens. The massive Persian army marched straight to Athens. Athens was not a walled city and it was essentially indefensible.

Themistocles wisely convinced the Athenians to evacuate Athens and escape to the Island of Salamis. The Athenians on Salamis watched as the Persians razed Athens and burned it to the ground.

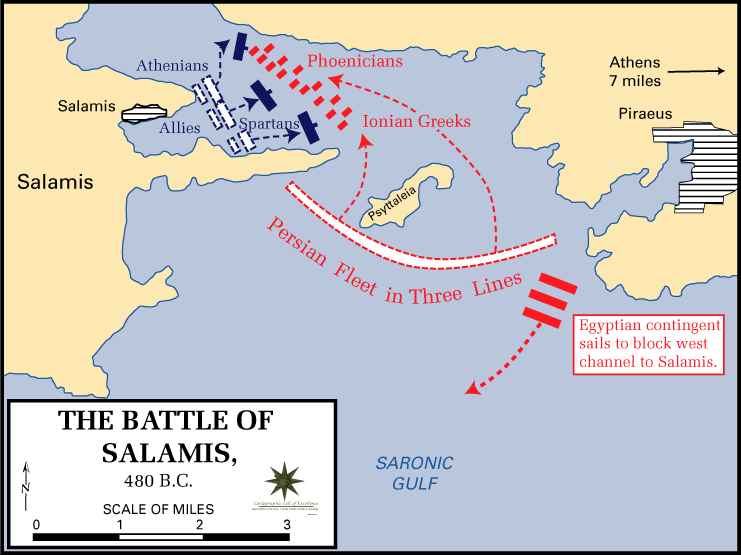

Meanwhile, Themistocles brought the Athenian Triremes into the narrow channel between Athens and Salamis. He then tricked the Persians into dividing their fleet, which had already been diminished in size by the Aegean storm mentioned above. The well-drilled and disciplined Athenian Navy became the “wooden walls” which were about to defend the people of the democratic Athenian city-state.

The Greek Triremes Rammed the Phoenician Damned

The Athenian Greeks who had been evacuated to the Island of Salamis were effectively surrounded by Persian forces. The Naval Battle of Salamis was led by the Athenian admiral, Themistocles is one of the most famous defensive naval battles in all of naval history.

The Achaemenid Persian emperor, Xerxes sat on a hill on the shore outside of Athens and he watched the battle unfold before him. The Greek fleet was arranged in several tight rows facing their attackers. The Persian fleet entered the channel and several Persian captains broke ranks with their fleet to execute a glorious and heroic individual attack on the impertinent Greeks, so their emperor could see their extraordinary courage.

The disciplined Greek sailors rammed each of those individual Persian ships and watched them sink while the seasoned Greeks rowed backwards into their own lines. Eventually the Persian admiral ordered a general but uncoordinated attack on the well-maintained Greek lines. The Greeks acted in coordinated unison and over several hours of fighting they sank many of the Persian-Phoenician vessels. The rest of the Persian fleet finally withdrew in defeat.

The Emperor Xerxes left Athens for home in shame. The remaining intact Persian vessels sailed for their respective home ports. The Greeks who had “rammed the damned” returned to Athens and began rebuilding their city using stone for all of their important buildings. The Athenian Triremes controlled the Aegean Sea for the next hundred years.

The golden age of Athenian democracy and Athenian culture flowered, and for the next 800 years (well into the age of Roman dominance) Athens was the educational center of the civilized Mediterranean world.